If you like sour beers, you’ve probably heard long, complicated yeast and bacteria names thrown around. They’re hard to spell, even harder to pronounce and can be down-right confusing to differentiate from one another.

If you like sour beers, you’ve probably heard long, complicated yeast and bacteria names thrown around. They’re hard to spell, even harder to pronounce and can be down-right confusing to differentiate from one another.

Many often refer to these bacteria and yeast unknowingly, so it’s worth taking some time to set the record straight. To understand these terms, we asked HBA (aka “The Mad Fermentationist”) for the inside scoop on each microbe.

Understanding Wild Fermentation

To begin, it’s key to understand the difference between wild and single-culture fermentation. Sour beers undergo wild or mixed fermentation, which means multiple yeasts and bacteria work together to create the funkiest of brews. In the category of wild ales, beers can be either controlled, meaning the brewers have selected exactly which yeast and bacteria to pitch, or open-air fermented, where fermenters are left completely or partially open to allow bacteria and wild yeast to enter.

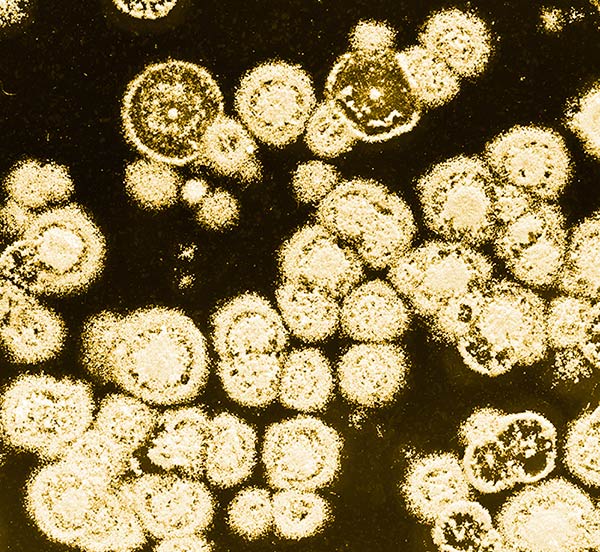

The yeast responsible for fermenting all clean beers is Saccharomyces, while Brettanomyces, Lactobacillus and Pediococcus are kind of the “Three Stooges” of sour beer production. They produce funky and sometimes hard to predict beers. There are also a variety of bacteria used to give sour beers the little extra something, too.

Saccharomyces

Saccharomyces, commonly known as brewer’s yeast, is the single genus of yeast responsible for fermenting all clean beers, but is also used in sour beer production. Brewer’s yeast is responsible for the greatest portion of gravity reduction and alcohol production in nearly all sour beers. There isn’t any wrong strain of brewer’s yeast that will ruin your beer, just some strains that work better with certain types of sour beers. Saccharomyces is a fast working, highly IBU-tolerant yeast that acts as a base yeast for sour beer production.

Overall, brewer’s yeast protects the wort and sets the stage for a traditional slow-moving wild fermentation.

Brettanomyces

Brettanomyces, often referred to simply as brett, is a genus of yeast, not bacteria as far too many brewers falsely believe. It is the principal wild yeast used in sour beer production. Specific flavors, aromas, esters and phenols produced in the beer depend on the strain and species of brett, ranging from pineapple and hay to horse blanket and acrid smoke. The beer’s character is also influenced by the acids and alcohols available to be combined into esters during fermentation. Tonsmiere referred to brett as the microbe that “doesn’t sour the beers you brew, it makes the sour beer you brew delicious.”

Brett also doesn’t contribute much to the acidity of sour beers, either. Acid production is the responsibility of bacteria. The only exception is when there is a large amount of oxygen available, which causes brett to produce acetic acid creating a vinegar-like sourness.

Brett serves the same function as Saccharomyces – it ferments beer. However, brett works more slowly, meaning a beer that could have fermented in a few weeks might take months or years to display its full character when brett is introduced. The great beer writer Michael Jackson once compared Saccharomyces to a dog and brett to a cat. Saccharomyces is trainable, usually predictable and comes back to you when called, while brett will run away when it feels like and will probably scratch you when you pick it up. In other words, it can be hard to predict and manage brett, but if you can respect the yeast for what it is and what it can do then you’ll be rewarded in the end.

Brett works well in tandem with the other microbes listed here, or on its own with a large enough pitch.

Lactobacillus

Lactobacillus, otherwise known as lacto, is also a bacteria, not a yeast. It acts similarly to a yeast in that it eats up sugars in wort, but rather than converting them to alcohol the sugars are converted to lactic acid. The lactic acid lowers the liquid’s pH rather quickly (sometimes within 24-48 hours), and gives beer a sour yet clean taste. Lacto is also found in plenty of food fermentations, like kimchee or yogurt. It creates a relatively clean taste since lacto doesn’t produce much besides lactic acid.

It’s most commonly responsible as the primary souring microbe in the German styles of Berliner weisse and Gose.

Pediococcus

Pediococcus, aka pedio, is also a bacteria, not a yeast. Pedio is the other common lactic acid bacteria used in sour beers, as well as in other culinary roles like the acidification of sauerkraut and traditional dried sausages. Pedio, unlike lacto, takes a long aging time to initiate a dramatic lowering in the pH of the beer, which works as an advantage because it allows time for the primary yeast strain to complete its fermentation before the substantial drop in pH occurs.

The draw back to acidifying with pedio is that most strains produce concentrations of diacetyl above the taste threshold. Unlike brewer’s yeast, pedio doesn’t reduce diacetyl by converting it to less-flavorful by-products. Instead, it leaves the buttery-popcorn flavor behind. A good remedy is to include brett in beers that are pitched with pedio, so it can eliminated diacetyl. This takes time, so be patient if your beer tastes like movie theater popcorn when it’s young.

Another major difference between lacto and pedio is the type of sourness they produce. While lacto produces a clean sourness, pedio can produce other funky aromas and flavors that result in a harsher sourness. However, pedio gives brett more fuel to work with, so they’re often used together. This bacteria is responsible for sour beers like lambic and Flander Reds.

Lactic Acid

Lactic acid is the primary acid in sour beers, along with carbonic acid from dissolved carbon dioxide, and is produced by lactic acid bacteria (specifically Pediococcus and Lactobacillus). It is mellow and tangy at low levels, but can be quite lip-puckeringly sharp at higher concentrations. It’s also the same acid found in yogurt, buttermilk and other tangy-sour dairy products. Lactic acid can also be turned into the fruity esters by brett. Tonsmiere described lactic acid’s character as “mostly on the tongue, rather than the back of the throat like acetic acid.”

Acetobacter

Acetobacter is less common bacteria, which is usually held to a minimum in the fermentation of most sour beers because it consumes ethanol to produce harsh-tasting acetic acid. These bacteria require a steady supply of oxygen to perform the oxidative fermentation that converts ethanol into acetic acid. It is also airborne, so even if you don’t pitch it, it can easily attach itself to your equipment that sits empty for several days or weeks.

Adding or allowing production of acetic acid pre-boil is not recommended because of its high volatility and nostril-stinging smell. Acetobacter won’t do much early in fermentation because carbon dioxide production prevents oxygen from coming in contact with the beer. However, after primary fermentation is complete, the lack of pressure will allow oxygen to start seeping in.

If you do desire a low level of acetic acid, which is an important flavor component of traditional Flemish reds and Belgian lambics, add a small amount of unpasteurized vinegar (contains live Acetobacter) when you pitch the other microbes.

from HBA