There’s nothing like the look of a creamy head on a homebrewed stout or the lacing on a glass after finishing a Belgian ale. But beer foam isn’t just about appearance. The bubbles from your beer impact carbonation level, aroma, flavor and body.

There’s nothing like the look of a creamy head on a homebrewed stout or the lacing on a glass after finishing a Belgian ale. But beer foam isn’t just about appearance. The bubbles from your beer impact carbonation level, aroma, flavor and body.

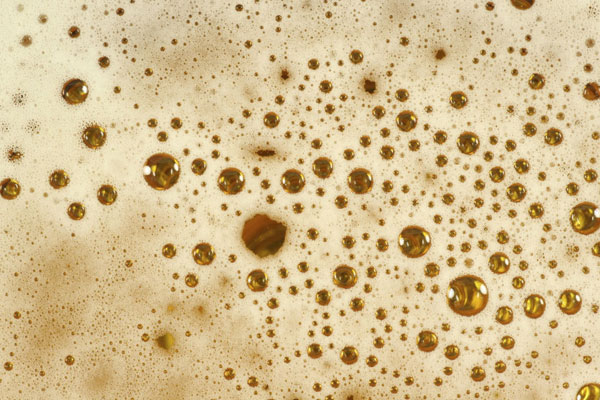

Beer foam is a complicated and far from understood phenomenon. So, what is foam? In short, foam is a dispersion of a relatively large amount of gas in a relatively small amount of liquid. It doesn’t happen spontaneously—it requires some energy by either agitating the beer (e.g. shaking or stirring) or creating a nucleation site (e.g. scratch on a glass or an engineered device) that allows bubbles to form and rise in the beer, sometimes referred to as “beading.”

So, how can homebrewers improve their beer foam?

Choose the Right Malt

Choose the Right Malt

Malts high in proteins and dextrin enhance the body and head retention of beer because the proteins act as a structural component in foam.

The malt-derived proteins are typically hydrophobic (water-hating), causing them to move up towards the foam where they encounter other positive foam stabilizing substances, like those from hops.

However, high levels of proteins and dextrins can interact with tannins and compromise clarity, provide more nutrients to spoilage microorganisms, and mean less fermentable extract per pound of grain (which means more money out of your wallet!). Finding a proper balance is the challenge.

Examples of foam-enhancing malts include crystal malts (e.g. Carapils, Carafoam, Caramel malts), as well as wheat malt. There is also some belief that dark malts (e.g. Chocolate) help improve foam stability because of their high levels of Melanoidin, a protein polymer which is formed when sugars and amino acids combine.

Adjust Your Mash Schedule

Head retention depends on the level of proteins in your wort. So, any step in the mash that breaks down these proteins will negatively affect your beer’s foam stability. For example, the typical protein rest at 120 – 130°F (49° to 54°C) is used to break up proteins which might cause chill haze and can improve head retention. However, this rest should only be used when you use moderately-modified malts, or fully modified malts with over 25% of unmalted grain (e.g. flaked barley, wheat, rye, oatmeal) because it will break down larger proteins into smaller proteins and amino acids, thereby reducing foam stability.

In contrast, fully-modified malts (most of what you’ll buy at a homebrew shop) have already made use of these enzymes and adding a protein rest will remove body and head retention. To improve head retention, you would want to favor a full bodied, higher temperature mash, with a main conversion in the 155 – 160°F (68 – 71°C) range, and avoid intermediate protein rests.

Hops

Hops

For all you hop-heads out there, here’s some more good news—hops help with foam stability. As mentioned above, the bitter substances from hops, isohumulones (a form of alpha acid), will help hold the bubbles together. These hydrophobic substances help form the framework for head formation.

However, this interaction doesn’t happen right away. You’ll notice when you pour a beer, the beer foam is wet and sloppy but changes to almost solid over a few minutes, in which the foam can adhere to the glass surface, otherwise known as “lacing.”

In other words, the longer you wait to slurp down your beer, the better your beer foam and lacing on the glass. Overall, highly-hopped beers should have better head retention, but remember to maintain a malt-bitterness balance.

Nitro Mix

As you may know, some beers are carbonated and poured with a mix of nitrogen and carbon dioxide (CO2). CO2 is relatively soluble in beer and therefore doesn’t promote the formation of bubbles as well as non-soluble gases (e.g. Nitrogen). Nitrogen is less soluble, so it tends to leave the beer and go directly to the foam, which reduces the permeability of gas through the bubbles and causes slower foam coarsening.

However, nitrogen will alter the character of the beer, giving it a creamy, thick mouthfeel and will also take away from some of the beer’s bitterness. Also bear in mind the percentage of each gas will depend on the style of beer you’re serving. Make sure to check what percentages work best with a particular style.

Glassware

Glassware

The glass you choose can influence head formation and head retention. A tall, narrow glass is a good choice because it minimizes exposure to ambient air, and reduces the ability for CO2 to escape.

In contrast, if you have a large opening on your glass, there is more air exposure, which allows CO2 to escape more easily. For example, many Bavarian wheat beers and Pilsners are served in tall narrow glasses to maintain head formation, retention and overall beer presentation.

This might seem obvious, but many beer drinkers forget about glassware. Your glassware should be “beer clean.” Follow proper cleaning procedures for beer glassware and avoid oil or grease. These substances will occupy space on the surface of the beer and prevent bubbles from forming. So next time your munching down a burger or putting on lipstick, make sure to wipe it off!

Other Factors

The Gush: Sometimes our beer begins gushing out the moment you pop it open. Most veteran homebrewers have experienced this. Next thing you know your pants and floor are soaked. This phenomenon is usually due to overpriming or microbial spoilage. Make sure to carefully measure priming sugar and practice good sanitation and this shouldn’t be a problem.

Temperature: Also, anything that increases the viscosity (thickness) of the beer should prevent foam from disappearing. Since viscosity increases as temperature decreases, colder beer has better foam stability. So make sure you pour your beer at a chilled temperature.

Better Beer Foam Tips

- Get your carbonation right.

- Choose malts with high protein levels (e.g. crystal malts, dark malts).

- Avoid low-protein adjuncts (e.g. corn, rice, sugar).

- Wheat malts and flaked barley will increase head retention.

- Bittering hops help with head formation.

- Sanitize and rinse your equipment well.

- Depending on the grain, mash at high enough temperatures.

- Nitrogen- CO2 gas mix can help with foam stability.

- Avoid fats and oils.

- Make sure glassware is beer clean.

- Carefully measure priming sugar.

- Serve beer chilled.

Overall, if you ensure that you provide your beer with as many foam enhancers as possible, you’ll end up with a delicious, good-looking beer.

Sources: How To Brew by John Palmer, “Positive Factors of Foam Stability” by Chris Bible May/June 2001 Zymurgy, Malt: A Practical Guide from Field to Brewhouse by John Mallet, and “Beer: Tap into the Art and Science of Brewing” by Charles Bamforth.

source: AHA