It’s a question that generates heated debates about the nature of these two styles. The real answer is a lot tamer than the debates.

It’s a question that generates heated debates about the nature of these two styles. The real answer is a lot tamer than the debates.

Just as regularly as the discussions about the difference between porter and stout appear on beer forums, someone quotes the Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) guidelines that identify the difference between the two as being the roasted malt employed: black malt for porter, roasted barley for stout. Unfortunately, the guidelines were written centuries after the fact and ignore how porter and stout were originally brewed.

To get to the root of the question, we have to travel back in time a couple of hundred years to the beginning of the eighteenth century, the time when porter and stout emerged as specific styles. In the classifications of the day, there were two types of malt liquor brewed: lightly hopped ale and heavily hopped beer. These were further subdivided by the base malt employed (pale, amber, or brown) and strength (small, common, and stout). The first porters and stouts were classified as types of brown beer—common brown beers and stout brown beers, respectively—meaning that they were well hopped and brewed from 100 percent brown malt.

A decade or so ago, I spent much time pondering the meaning of the term “brown stout.” Why did some brewers call their stouts by this name? The answer was stunningly simple: Until the nineteenth century, brown stout wasn’t the only type of stout. There was also pale stout, a beer of similar strength brewed from pale malt. Stout meant nothing more than “strong,” and the brown qualifier was needed to tell you what type of beer to expect.

You’ve probably spotted why the black malt/roasted barley differentiation couldn’t have applied to the first porters and stouts: neither contained either of those grains in the 1700s. Black malt was specifically developed in 1817 to color porter and stout after burnt sugar coloring was made illegal in 1816. That same law also explains why roasted barley wasn’t used in British brewing until the end of the nineteenth century: the law outlawed the use of unmalted grain.

One of the most annoying stories knocking around the Internet is that Arthur Guinness used roasted barley because it wasn’t taxed. There are just a few problems with that tale. For a start, roasted barley wasn’t developed until long after Mr. Guinness’s death in 1803. And had Guinness been found with roasted barley on the premises before 1880, it would have been in big trouble, facing huge fines and possible confiscation of its equipment. The truth is that Guinness only started using roasted barley in the twentieth century. It’s often forgotten that until the 1970s Guinness also brewed a porter. It contained the same roasted grain—black malt or roasted barley, depending on the date—as its Extra Stout.

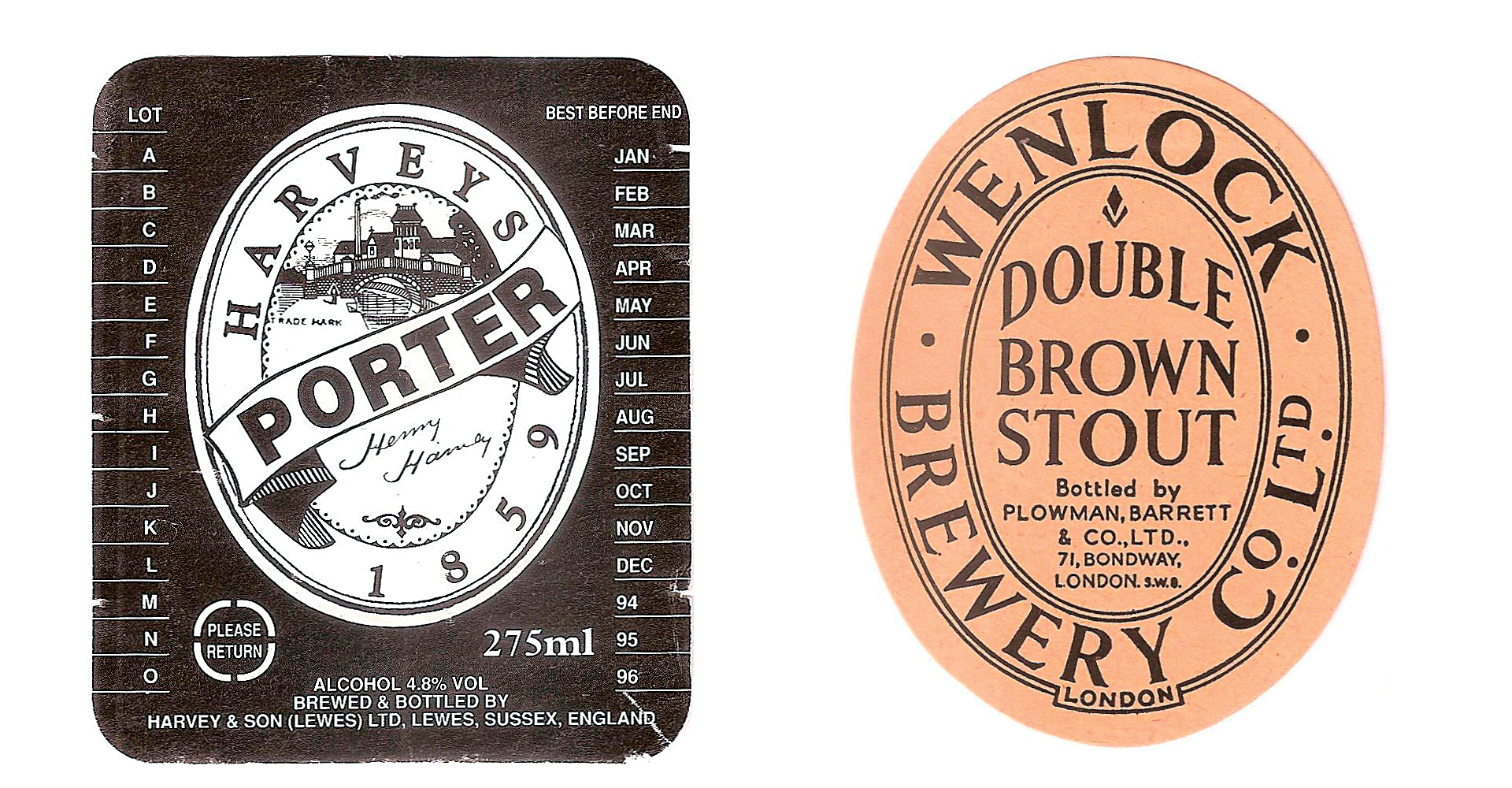

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, London brewers didn’t really have separate recipes for their porters and stouts. Even when they weren’t parti-gyling them, they still used pretty much exactly the same recipe. The only variable was the amount of water used. Porter was the name used for the weakest beer in the stout family.

So why all the confusion today? I blame World War I. It had two effects that are relevant here. First, it sent British porter into terminal decline. Second, it caused British beer gravities to tumble. The combination of the two obscured the pattern in the relationship between the two styles. After World War II, few breweries in the world made both a porter and a stout. Reduced gravities meant that British-brewed stouts were often weaker than foreign porters.

Historically, there was no difference between porter and stout in terms of ingredients or brewing methods. Simply put, porter from a particular brewery was always weaker than the same brewery’s stout.

from Beer&Brewing