Here’s How A Six-Pack Of Craft Beer Ends Up Costing $12

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: There’s never been a better time to be a beer drinker in America. The skillful innovation of American craft brewers over the past decade has pushed beer in delicious new directions. It wouldn’t be hard to argue that the craft beer renaissance is the most exciting development in the country’s culinary world right now.

But this explosion in quality comes at a price. Literally. With few exceptions, prices for good craft beer are far higher than for mainstream macrobrews from brewing conglomerates such as MillerCoors and Anheuser-Busch. A six-pack of beer from breweries like Dogfish Head, Ballast Point or Cigar City almost always costs more than $10 — and routinely exceeds the $15 mark. You could easily get a 12-pack of Bud Light for that much.

Part of the price differential is due to pure marketing. Like vendors of designer clothing, acclaimed craft breweries can charge more because their customers expect to pay more for luxury goods. I recently spoke with more than a dozen people involved at all levels of the craft beer world to get a sense of the industry’s cost structure. It turns out that craft brewers incur far higher costs than mainstream brewers. Indeed, once you learn about all the work and material that goes into each six-pack, $12 starts to seem like a bargain.

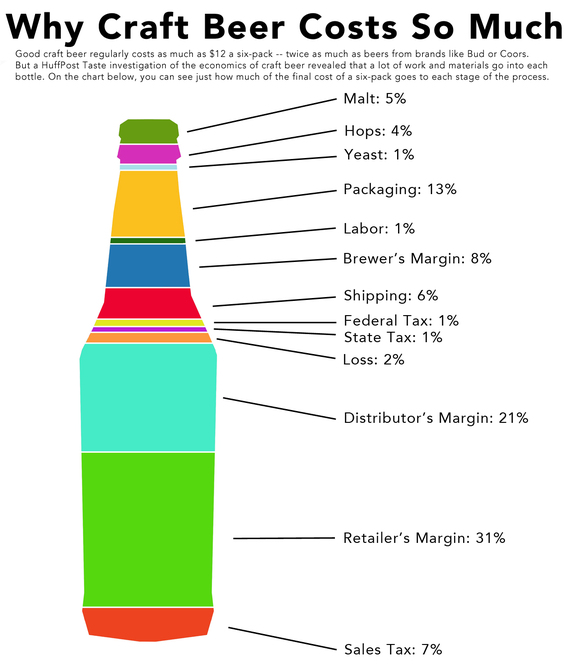

Here’s an infographic that summarizes my findings, showing how much of the final cost of a typical six-pack of craft beer is due to each expense:

To give you a sense of what all these various expenses actually mean, I’ll take you through the life cycle of a craft beer — from grain to glass — explaining, at each step, what’s involved.

Raw Ingredients

Most beers contain four basic raw ingredients: water, malt, hops and yeast.

Beer brewing uses a great deal of water. About five gallons are required to produce one gallon of beer. And water access has become a problem for some growing craft breweries on the West Coast, which has been experiencing a major drought for the past couple years. But even in Southern California, water remains so cheap that it’s not a serious concern for most breweries when it comes to pricing. So we’ll leave that out of the equation.

The other three ingredients cost real money. Let’s take them one at a time.

Malt: When it comes to malted grain — the source of the sugars that become the alcohol that makes beer what it is — macrobreweries have three key advantages over craft breweries. Their huge size lets them demand lower prices from malt suppliers. They mix corn or rice — far cheaper than the traditional barley — into their beer. And compared with craft breweries, they generally produce beers that are lower in alcohol, which require significantly less malt per barrel of beer. Craft breweries are also likely to use small amounts of specialty malts to add special flavors to the final product.

According to Bob Hansen, an executive at specialty malt powerhouse Briess, a medium-sized craft brewer can expect to pay 40 cents to 50 cents per pound for malt, while a macrobrewer will pay closer to 22 cents a pound. And while a macrobrewer uses about 40 pounds of malt to make a barrel of low-alcohol beer, a craft brewer might use 70 pounds to 100 pounds of malt to make a barrel of IPA or stout.

That means that a six-pack of craft beer contains about 65 cents of malt, while a six-pack of macrobrew contains about 16 cents of malt.

Hops: Hops are the herbacious plants that contribute much of the distinctive flavor to great beer, especially the hoppy IPAs that are the bestselling category in the craft beer world. They’re best known for adding bitterness to beer, but there are hundreds of varieties of hops, each of which contributes its own flavor to beer. Certain hop varieties have become extremely sought after by craft brewers in recent years, driving prices to record levels. Though most hops cost $4 to $6 a pound, some specialty types cost as much as $20 a pound.

Macrobrews contain almost no hops; that’s why they taste so “drinkable” and un-bitter. A macrobrewer might add a pound of cheap — say, $3 a pound — hops to a barrel of beer. Meanwhile, a craft brewer could easily put four pounds of $7-a-pound hops into a barrel of hoppy IPA.

All told, a typical six-pack of craft beer contains 53 cents worth of hops, while a six-pack of macrobrew contains maybe 5 cents. And, of course, the sky’s the limit on the craft beer side. A super-hoppy double IPA with ultra-premium hops could include more than $1 worth of hops.

Yeast: Another category that ranges wildly in price. Very large brewers — and some craft brewers — cultivate their own yeast, and rarely spend significant money on it. So let’s call a macrobrewer’s yeast cost nil.

But most others regularly buy fresh batches of yeast from the two companies that produce it for the beer market: San Diego’s White Labs and Oregon’s Wyeast. Overnighting a batch of yeast large enough to brew a 30-barrel batch of beer is extremely expensive — around $800. Most brewers try to reuse the yeast as many times as possible, often around four times, which would imply a per-six-pack cost for yeast of 13 cents. It’s less than malt or hops, but still significant.

It should be noted that a few breweries — including hugely acclaimed Toppling Goliath brewery in Decorah, Iowa — insist on buying fresh yeast every time they brew beer. Clark Lewey, the owner of Toppling Goliath, said the increased quality and consistency more than justifies 50 cent-per-six-pack cost of fresh yeast.

Additional Ingredients: Some specialty beers made by craft brewers include additional ingredients as supplemental flavorings. Coffee beans, for example, make regular appearances in certain stouts, and spices like grains of paradise and chipotle peppers have been known to add zest to various beers. In some cases, these ingredients can add as much as a couple dollars to the cost of a six-pack. The range here is too big to include in our normal analysis, especially because most beers don’t include anything besides the big four, but it can be a major factor in the price of some beers.

Brewing, Aging and Packaging

Once all the raw ingredients get to a brewery, the beer-making can begin. That requires labor. Several people I spoke with cited a rule of thumb for labor costs that says it takes about 20 hours of work to make a batch of beer, regardless of the size. The going rate for a ground-level brewer at a non-union brewery is about $12 an hour, meaning it costs $200 in labor to make a batch. Assuming the 30-barrel batches that are standard at relatively small breweries, that means 15 cents of labor goes into a typical six-pack of craft beer.

Packaging — whether in cans or bottles — is surprisingly expensive. Even buying in bulk, a glass bottle with a beer label affixed to it can cost as much as 20 cents, and the cardboard container that holds a six-pack costs a few more cents. So packaging can add as much as $1.50 to the cost of a six-pack. Packaging is often one of the single-biggest expenses a brewery incurs. That amount drops significantly when a brewery is selling beer by the half-barrel to restaurants, but it’s still considerable.

Some high-end beers undergo barrel-aging for six months to a year before being bottled. A brewery has to buy a barrel, usually from a bourbon distiller, for about $100, for this process. In addition, it takes up valuable time and space in the brewery, which is hard to quantify. Let’s assume barrel aging adds about $1 to the final cost of a six-pack. But because relatively few beers undergo barrel-aging, we won’t include this cost in our main analysis.

Finally, buying equipment and renting space for a commercial-scale brewery costs a ton of money — at least several hundred thousand dollars, and often in excess of $1 million. And there are ongoing costs — promotional events, advertising, R&D — that are not included in the small amount of labor mentioned above.

Basic microeconomics tells us that it’s unwise to explicitly account for these past expenses, called sunk costs, when pricing a product, but the owner of the brewery eventually has to recoup that investment, not to mention make a living. To do that, breweries typically add a healthy markup to costs before selling the beer to a distributor — around 50 percent of gross costs, leading to a margin of 33 percent. Assuming raw ingredient costs of $1.31, labor costs of 15 cents and packaging costs of $1.50, the brewer’s margin ends up adding about 91 cents to the final cost of the six-pack.

Shipping

A brewery that mostly sells its beer in-state, or in a relatively tight group of states, won’t incur much in the way of shipping costs. But prominent craft breweries are increasingly distributed across the country. You can now find beer from lots of San Diego and Portland breweries in New York City, for example. And trucking beer thousands of miles costs a lot of money.

Andreas Martin, a transportation broker specializing in the beer industry, said shipping costs vary significantly by season. Refrigerated trucks out of California are far more expensive in the summer, when vegetable producers in the Central Valley and Salinas Vally are competing for them. Martin said that, depending on the time of year and the type of truck, it costs $5,000 to $7,000 to send a truck across the country. A truck generally carries 18 pallets of goods, and you could fit around 80 cases of beer onto one pallet. That translates into shipping costs of 67 cents for each six-pack trucked across the country.

Excise Taxes

The federal government and each state government levy excise taxes on all alcoholic products, and beer is no exception. Federal excise tax is the rare cost that’s actually lower for small breweries than large ones. Washington charges breweries $7 per barrel for the first 60,000 barrels a brewery sells. After that — and for all breweries that sell more than 2 million barrels a year — the federal tax is $18 a barrel.

States vary wildly in the amount they levy, from 62 cents a barrel in Wyoming to $33 in Alaska. The median, though, is $6.20, which is what we’ll use for the purpose of our analysis.

Federal and state excise taxes add about 23 cents to the price of a six-pack.

Distribution

Thanks to a web of laws created in the wake of Prohibition, almost all beer sold in America must pass through a distributor before it reaches a consumer. Beer distributors are in charge of a wide variety of tasks: They help market beers to restaurants and shops, they teach retailers the proper way to serve beer, and they bring beer from their warehouses to retail locations. They’re generally accountable for any loss along the supply chain — theft, broken bottles and so forth — which might account for about 5 percent of the total.

For these services — and thanks to their legally-mandated monopoly, they generally mark beer up drastically — 50 percent is normal. All the costs we’ve discussed so far mean that a distributor might buy a six-pack from a brewer for $4.75. The distributor’s markup, plus the cost of the lost product, adds $2.73 to the price of a six-pack.

Retail

A typical retailer, then, would buy a six-pack of craft beer for about $7.48 from a distributor. The retailers I spoke with for this article said that, for sought-after craft beers, there’s relatively little wiggle room on pricing at this stage, even for large companies. But as anyone who’s comparison-shopped beer within a given city can attest, they have broad discretion on how much they will charge the consumer. A run-of-the-mill bottle shop is likely to mark up beer by around the same amount as the brewery and the distributor — that is, 50 percent, or $3.75 on a $7.48 six-pack. Once you add the 7 percent sales tax, approximately the national median, you get almost exactly $12 a six-pack.